Summary

J.C. Bose was a quiet listener to nature. Living under British rule, he explored ideas many refused to accept. He showed that plants respond to touch, pain, and rest, much like animals. Long before wireless technology became widely known, he worked with radio waves. Bose never chased wealth or fame. He believed knowledge should be shared freely. His life was shaped by patience, courage, and deep respect for all forms of life.

Table of Contents

J.C. Bose’s Early Life: Where His Thinking Began

Jagadish Chandra Bose was born on 30 November 1858 in Mymensingh, then part of British India. His father, Bhagawan Chandra Bose, believed education should remain close to one’s roots. Instead of sending his son to an English school, he chose a village school.

There, young Jagadish studied alongside children from different communities. This early experience shaped his sense of equality and humility. These values stayed with him throughout his life.

His mother, Bama Sundari Devi, supported him quietly but firmly. During times of financial hardship, she pawned her jewellery so her son could continue his studies. Bose later remembered her patience and strength with deep gratitude.

Growing up in Bengal, he absorbed its language, culture, and thought. This grounding helped him remain steady when colonial systems tried to limit Indian voices.

Education: Learning Far From Home

Bose studied science at St. Xavier’s College in Calcutta, where his teachers noticed his calm focus and careful thinking. After completing his studies in India, he travelled to England to continue his education.

He first enrolled in medicine but was forced to leave due to ill health. In 1882, he joined Christ’s College, Cambridge, to study natural sciences. He also earned a science degree from the University of London.

Though he performed well, Bose often felt overlooked in British academic spaces. He chose not to dwell on this. Learning mattered more to him than recognition.

College Years and Early Career

After returning to India, Bose joined Presidency College in Calcutta as a professor of physics. Here, he faced open discrimination. British professors were paid more, while Bose was offered a lower salary because he was Indian.

He responded with a quiet but firm protest. Bose continued teaching without accepting his salary for nearly three years. Eventually, the injustice was corrected.

This moment revealed his character. He valued dignity over comfort and principle over position.

Working Under British Rule

Colonial rule placed many limits on Indian scientists. Bose was often denied proper laboratory space and equipment.

Undeterred, he carried out experiments in a small room measuring just 24 square feet. He designed and built his own instruments, working with patience and discipline. What he lacked in resources, he made up for through careful observation and steady effort.

Gradually, his work began to draw attention beyond India.

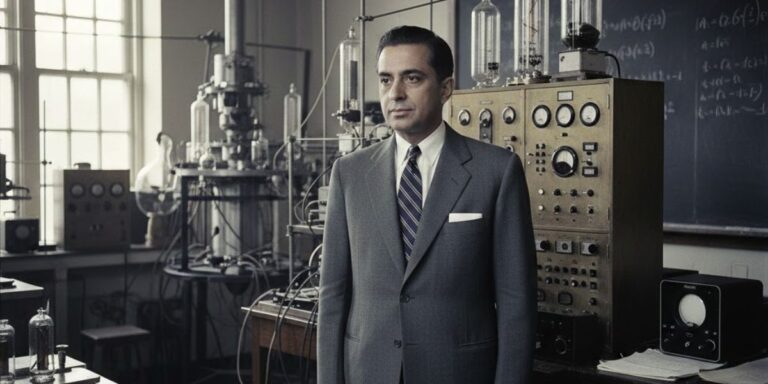

J.C. Bose and His Work in Physics

In 1895, Bose demonstrated the wireless transmission of electromagnetic waves. These waves travelled through air, walls, and even the human body, covering a distance of about 23 metres.

This work came before similar demonstrations by Popov and Marconi. Yet Bose showed little interest in turning this discovery into a commercial system. He was drawn to understanding nature, not to building wealth.

He worked with very short radio waves, now known as microwaves. Bose designed antennas, waveguides, and polarizers—ideas that later became central to modern science. At Cambridge, he even suggested that the Sun might emit electromagnetic waves, a thought far ahead of its time.

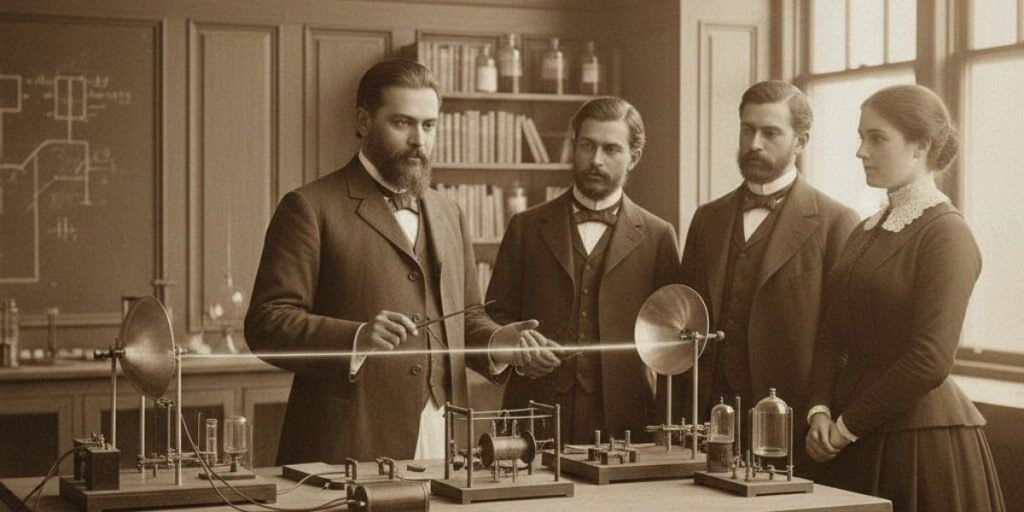

Inventions, the Coherer, and His Stand Against Patents

To detect radio signals, Bose invented a coherer using mercury inside a metal cup. This device functioned as an early semiconductor detector.

In 1904, he received a U.S. patent for this invention, becoming the first Asian to do so. Still, Bose remained uneasy about patents. He believed that locking knowledge behind ownership slowed human progress.

He applied for the patent only after close friends, including Rabindranath Tagore, urged him to protect his work from misuse. Most of his inventions were never patented. He shared his ideas openly, allowing others to build upon them freely.

A Turning Point: From Physics to Plants

While studying metals, Bose noticed something unexpected. His instruments showed signs of fatigue after long use. After rest, they regained sensitivity.

This observation led him to a simple question.

If metals could respond to stress, could plants respond too?

This quiet question changed the direction of his life’s work.

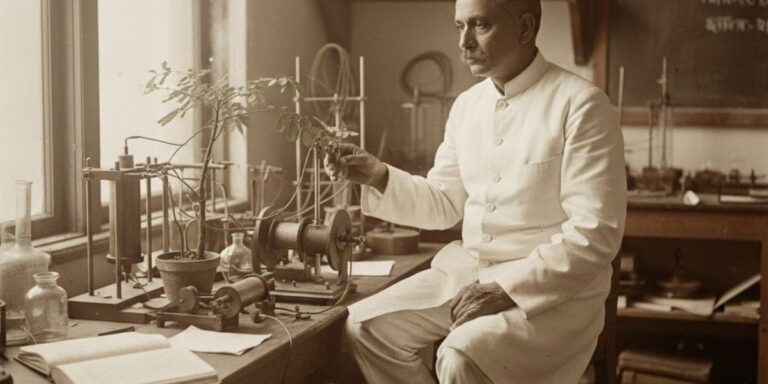

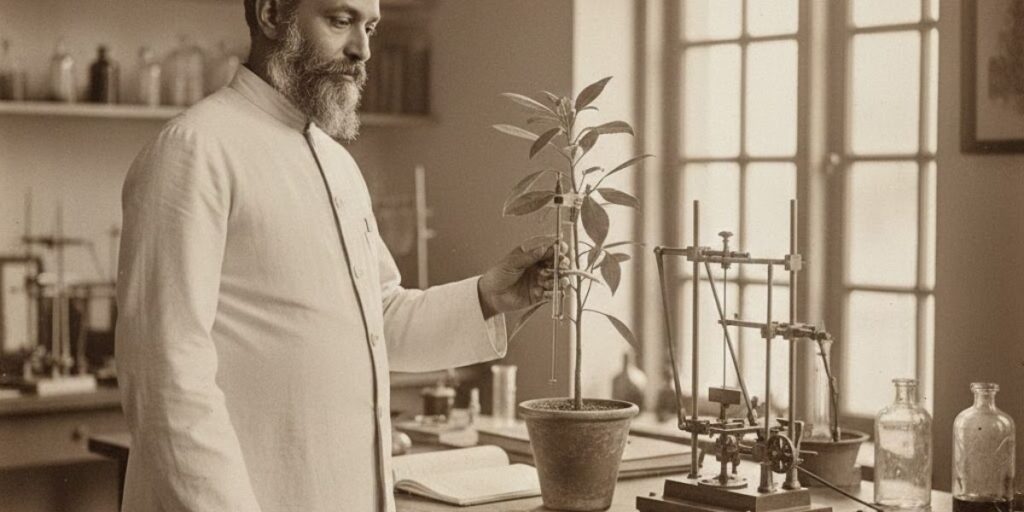

Plant Physiology and the Crescograph

Bose began studying how plants respond to touch, heat, injury, and chemicals. While working at the Davy-Faraday Research Institute in England, he carried out early experiments using leaves and vegetables from his garden.

In 1900, he presented a paper in Paris showing that plants respond through electrical signals. Many scientists were surprised. Some were doubtful. A few dismissed his findings outright.

Bose did not argue. He returned to observation and measurement.

Swami Vivekananda attended the lecture and praised his insight. Rabindranath Tagore later honoured his work through poetry.

Bose showed that plant responses were electrical rather than purely chemical. Plants treated with poison or anesthetics showed little reaction.

To measure these minute movements, he invented the Crescograph, an instrument capable of recording growth invisible to the human eye. This work laid the foundation for modern plant physiology.

Facing Doubt and Scientific Resistance

Bose’s shift from physics to plant studies puzzled many scientists. Some believed scientific fields should remain separate. Others doubted that plants could show such sensitivity.

Recognition came slowly. Several of his ideas were accepted only decades later, when science had advanced enough to understand them fully. Bose endured this resistance quietly, trusting evidence more than approval.

Seeing Life as One Whole

Bose believed that all matter, living and non-living, responds to its surroundings. He refused to divide science into rigid subjects.

He designed many instruments to explore this idea, several of them made in India. His books Response in the Living and Non-Living and The Nervous Mechanism of Plants expressed this integrated view of life. The latter was dedicated to Rabindranath Tagore.

Personal Life and Values

Jagadish Chandra Bose married Abala Bose, an educationist and social reformer who stood beside him through years of quiet work. Their partnership was built on shared values of education, dignity, and service.

They did not have children of their own. Bose never saw this as an absence. His care flowed into his students, his research, and the living world he studied. He observed plants with patience and respect, almost like a guardian rather than a controller.

He lived simply and avoided public attention. For Bose, science was a responsibility, not a path to fame.

Bose Research Institute

In 1917, Bose founded the Bose Research Institute in Calcutta, giving form to a long-held dream. He imagined it as a place where learning could grow freely, without fear or rigid boundaries.

At a time when Indian science was shaped by colonial priorities, Bose wanted an institute guided by curiosity and honesty. He encouraged work across disciplines, believing physics, biology, and life studies were deeply connected.

Many instruments used at the institute were designed and built in India. This reflected his belief that original research did not need foreign approval. Even today, the institute stands as a living reflection of his values.

Later Years and Passing

Bose spent his later years teaching, writing, and guiding students. He passed away in 1937.

Only later did the world fully recognise how far ahead of his time he had been.

Legacy and Recognition Beyond Earth

Jagadish Chandra Bose was widely honoured for his scientific work. He was knighted in 1917 and became a Fellow of the Royal Society of London in 1920, the first Indian physicist to receive this honour. He later led the Indian Science Congress and was elected to leading science bodies in Europe.

Bose also represented Asia on a global science committee alongside figures like Einstein and Marie Curie. In recognition of his lasting impact, a lunar crater on the Moon was named after him.

Today, modern science continues to confirm many of his ideas. His work influences plant science, bioelectric research, and wireless technology.

Key Takeaways

- Bose showed that plants respond like living beings

- He worked on wireless science before it became widely known

- He chose shared knowledge over profit

- His life stood for patience, dignity, and moral courage

Citations

1. Vajiram & Ravi, Jagadish Chandra Bose – Life, Work and Contribution 2. Encyclopaedia Britannica, Jagadish Chandra Bose

3 . Bose, J. C., Response in the Living and Non-Living (1902) 4. Bose, J. C., The Nervous Mechanism of Plants (1926)

5. Bose Research Institute, Kolkata – Official history and archival material

Read More about Indian Legends:

Vikram Sarabhai’s Rocket Roots: Space Pioneer Who Planted Thumba’s Coconut Launchpad