Summary

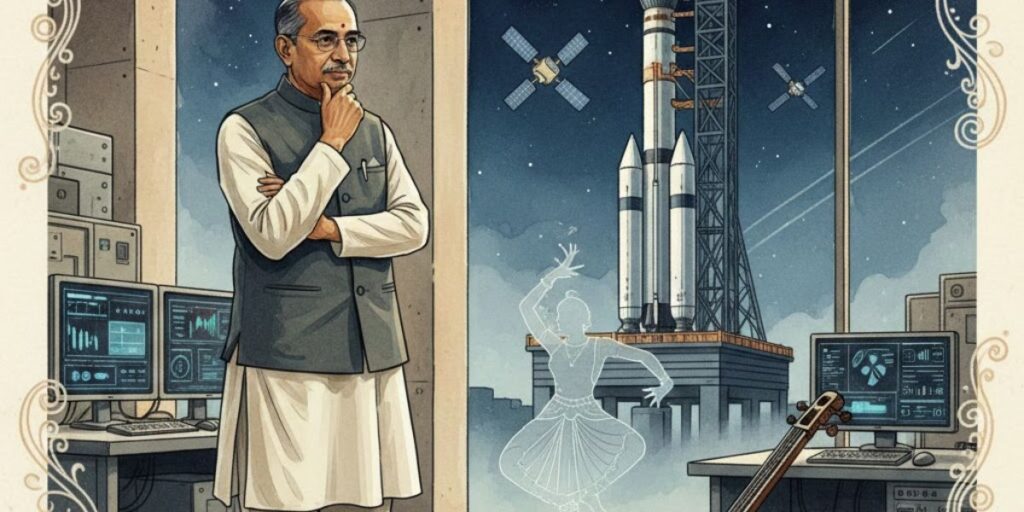

Vikram Sarabhai, the father of India’s space programme, believed that science should directly help society. When India was struggling with poverty and limited resources, he imagined using space technology for education, communication, and national development. From a curious childhood to launching rockets from coconut groves at Thumba, Sarabhai built a space programme focused on people, cooperation, and long-term progress, laying a strong foundation for India’s future in space.

Table of Contents

Vikram Sarabhai’s Life Stories and the Roots of a Vision

A Childhood Shaped by Curiosity

Vikram Ambalal Sarabhai was born on 12 August 1919 in Ahmedabad. He grew up in a family deeply engaged in industry, education, and social reform. His parents, Ambalal Sarabhai and Sarla Devi, believed that knowledge carried a duty toward society. Their home was a meeting place for scientists, artists, thinkers, and leaders of the freedom movement. As a child, Sarabhai absorbed conversations that moved naturally between science, culture, and ideas about India’s future. This atmosphere encouraged independent thinking and calm confidence.

His early education followed the Montessori method. Learning was guided by curiosity rather than strict discipline. Children were encouraged to explore, experiment, and learn through experience. Fear of failure was largely absent. This approach shaped Sarabhai’s lifelong love for learning and innovation.

From a young age, he showed a strong interest in science and mathematics. At the same time, he became aware of social inequalities around him. These early impressions planted a lasting belief that science must remain connected to human needs.

Education and Exposure to Global Science

Sarabhai continued his studies at Gujarat College in Ahmedabad, where he pursued science. His academic promise soon took him to England. He enrolled at St John’s College, University of Cambridge, and studied Natural Sciences, graduating in 1940.

At Cambridge, he worked in modern laboratories and interacted with scholars from many countries. He learned discipline, teamwork, and long-term planning. Yet his attention remained fixed on India and its future.

The outbreak of World War II forced him to return home earlier than planned. Instead of continuing his work abroad, Sarabhai chose to build his career in India. He believed the country needed scientists who understood its realities.

He joined the Indian Institute of Science in Bengaluru and worked under C.V. Raman on cosmic ray research. Though equipment and funding were limited, the intellectual environment remained strong. This experience strengthened his belief that commitment and ideas mattered more than expensive resources.

Early Scientific Work and a National Outlook

Sarabhai’s scientific work earned recognition, but his ambitions extended far beyond academic success. He constantly reflected on how science could support a newly independent nation.

In the 1950s, India struggled with poverty, uneven education, and weak communication systems. Many believed advanced scientific research was a luxury the country could not afford.

Sarabhai firmly disagreed. He believed science and technology were essential tools for development. For him, space research was not about prestige or global competition. It was about addressing real and urgent problems.

Unlike space programmes in developed nations, Sarabhai imagined an Indian programme shaped by social needs. He spoke of using satellites for education, agriculture, weather forecasting, health awareness, and communication. His ideas were practical, inclusive, and focused on people.

Building a Space Programme Amid Scarcity

When Sarabhai proposed investing in space technology, India was still struggling to meet basic needs. Critics questioned spending on rockets when food, housing, and education demanded attention.

Sarabhai explained that space technology could help solve these very problems. Satellite communication could reach villages far faster than ground-based systems. Educational broadcasts could overcome barriers of language and distance. Weather data could support agriculture and planning.

In 1961, he began presenting India’s vision of space research on international platforms. He spoke of a television system with one visual channel and multiple audio tracks to serve India’s many languages. He imagined satellites supporting education, health, family planning, and communication across the nation.

INCOSPAR and the Institutional Beginning

In February 1962, Sarabhai helped establish the Indian National Committee for Space Research (INCOSPAR) under the Department of Atomic Energy. This marked the formal beginning of India’s space programme.

INCOSPAR began with limited funds, borrowed buildings, and a small group of young scientists. Sarabhai created a work culture based on trust, openness, and responsibility. Young engineers were encouraged to think independently, and mistakes were treated as part of learning.

This approach later shaped the work culture of the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO).

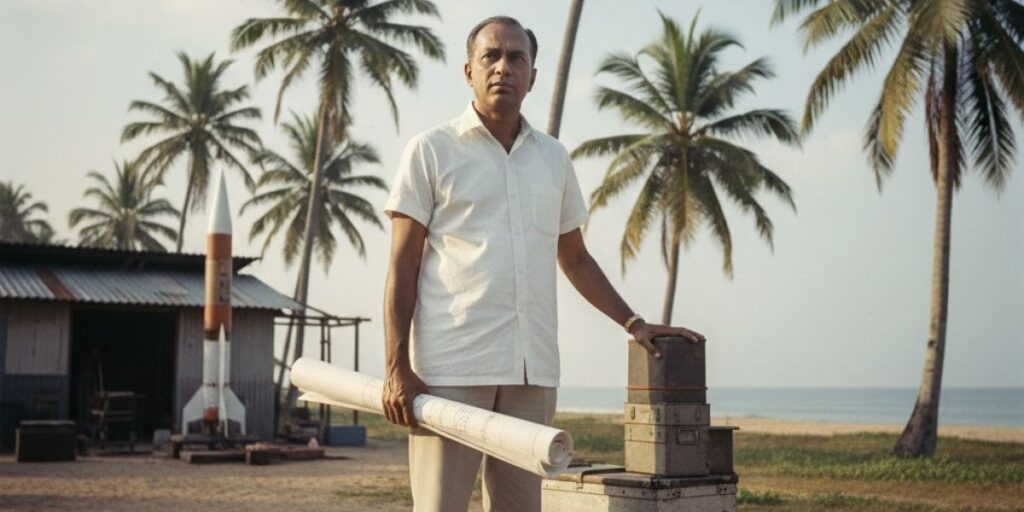

Why Thumba Was Chosen

Sarabhai selected Thumba, a small fishing village near Thiruvananthapuram, as India’s first rocket launch site. Its location near the magnetic equator made it ideal for studying the upper atmosphere. Thumba was simple and quiet, surrounded by coconut trees and the sea. At its centre stood a small church. Sarabhai met the local fishing community and explained the purpose of the project. Through open dialogue and trust, the fishermen agreed to relocate nearby. With the support of the local Bishop, the church was converted into a space laboratory. In 1963, the Thumba Equatorial Rocket Launching Station (TERLS) was established, becoming a symbol of cooperation between science and society.

The First Rocket Launch and Its Challenges

Preparing for India’s first rocket launch was difficult. Equipment arrived from different countries and often did not fit together. Facilities were basic, and improvisation was required at every stage.

What made the effort remarkable was international cooperation. Despite Cold War tensions, the United States supplied the Nike Apache rocket. A computer came from Minsk, a helicopter from the Soviet Union, and scientific support came from France.

The sodium vapour payload was personally carried to India by Professor Jacques Blamont. This cooperation reflected Sarabhai’s belief that science should rise above political divisions.

On launch day, several problems arose. A hydraulic crane failed, forcing the rocket to be positioned manually. Soon after, it became clear that the payload did not fit the nose cone. A young engineer worked through the night, carefully filing it to size. That engineer was A.P.J. Abdul Kalam.

On 21 November 1963, at 6:25 PM, the Nike Apache rocket lifted off. It released a bright orange sodium cloud visible to the naked eye. The sight captured public attention. Even the Kerala Legislative Assembly paused briefly to observe the event.

Space Science for National Development

Sarabhai consistently argued that space science must serve national goals. He believed satellites could deliver education to millions faster than traditional methods and improve communication across regions.

He encouraged scientists to apply their skills to practical problems. For him, research mattered only when it improved everyday life.

India later promoted peaceful and cooperative space research at the United Nations, reflecting Sarabhai’s belief in shared global progress.

Cultural Significance of Sarabhai’s Vision

Science as a Tool for Nation-Building

Sarabhai changed how India viewed science. Before him, advanced research was often associated with prestige or elite institutions. He gave science a clear social purpose.

Even during times of poverty and limited resources, he believed science must address real problems. Rockets and satellites were tools of development, not symbols of power.

Space Technology for Education and Social Change

Sarabhai believed education was the foundation of national progress. He understood that traditional systems alone could not reach millions quickly.

This belief led to the Satellite Instructional Television Experiment (SITE). Through satellite broadcasts, educational programmes reached rural villages. Farmers learned improved practices, families received health information, and children gained access to learning.

Satellites became classrooms in the sky.

Building Institutions, Not Personal Glory

Sarabhai focused on building institutions that would last beyond individuals. He helped establish organisations that became pillars of Indian science. These institutions valued ideas and responsibility more than hierarchy. Young scientists were trusted with major roles, building confidence and a sense of ownership

Bridging Science, Art, and Culture

Sarabhai believed science and culture must grow together. He felt national development required creativity as much as technology. This belief led him to establish the Darpana Academy of Performing Arts. It provided a modern platform for Indian classical and contemporary art forms.

A New Scientific Ethos for India

Sarabhai shaped a scientific culture based on humility, cooperation, and service. The international collaboration seen in India’s early space efforts reflected this attitude. For him, science was a shared human endeavour.

Recognition, Awards, and Living Landmarks

Sarabhai never worked for personal recognition, yet his contributions were widely honoured. In 1962, he received the Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar Award for contributions to physics. In 1966, he was awarded the Padma Bhushan. He was posthumously honoured with the Padma Vibhushan in 1972.

His legacy also lives on through lasting landmarks. The Vikram Sarabhai Space Centre in Thiruvananthapuram continues his vision. Beyond Earth, a crater on the Moon bears his name. India’s lunar mission further honoured him by naming the Chandrayaan lander “Vikram.”

The Final Years and an Untimely Loss

In his final years, Sarabhai carried immense responsibility. He guided India’s space programme, built institutions, and managed international partnerships. Rest was rare, and the pressure was constant. C.V. Raman once described his life as “burning both ends of the candle.”

On 30 December 1971, Sarabhai passed away suddenly at the age of 52 while staying at Halcyon Castle in Kovalam. He had spent the day reviewing space programme work and was preparing to travel. His death was caused by a cardiac arrest linked to extreme stress and exhaustion. At the time, he was deeply involved in the Aryabhata satellite programme.

Vikram Sarabhai: The Enduring Spirit of the Coconut Launchpad

India’s achievements in space trace their roots to Thumba. Among coconut trees and borrowed rooms, Sarabhai planted not just rockets, but belief in possibility. Through vision, patience, and quiet determination, he taught India to look beyond limitations and reach for the stars.

Key Takeaway

- Vikram Sarabhai viewed science as a tool for social development.

- His Montessori education shaped curiosity-driven leadership.

- He pursued space research despite economic hardship.

- Thumba symbolised science built on trust and cooperation.

- He focused on institutions rather than personal glory.

- International collaboration reflected his belief in peaceful science.

- His legacy continues through ISRO, lunar landmarks, and space missions.

Citations

Department of Space, Government of India. Vikram Sarabhai: Father of the Indian Space Programme.

Indian National Science Academy. Biographical Memoir of Vikram Ambalal Sarabhai.

McCray, W. Patrick. Vikram Sarabhai and the Rise of India’s Space Programme.

ISRO Official Website. History of TERLS and Early Rocket Launches.

NASA Lunar Nomenclature Database. Sarabhai Crater. Britannica: Vikram Sarabhai established the Indian National Committee for Space Research in 1962.

Read More About Indian Legends:

C.V. Raman’s Nobel Blue: Scientist Proved Sky’s Color with River Light